THE TAROT WHEEL

LO IMPICHATO - THE HANGED MAN

The head of a young man hanging upside down. He is part of one of the most intreaging cards of the Tarot, the Hanged Man. According to the Sermones de Ludu cum Aliis, the oldest (~1470) known list of the Trump names, the card is called Lo Impichato (l'impiccato), that can be translated to the hanged man, so exactly the same name as we are using today. The image here above is a detail of one of the two surviving corresponding Trionfi cards, the so called Charles VI Tarot, created in Ferrare in the 15th Century for the ruling Este family. The entire card and the other surviving card are shown here below.

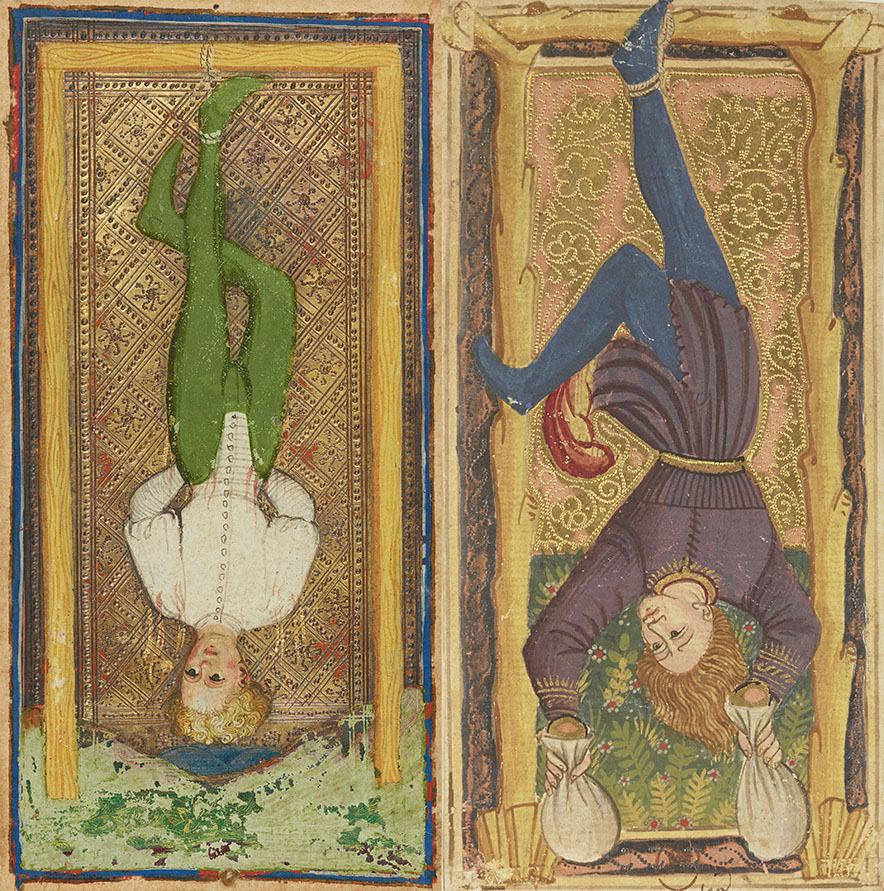

At the left we have the Hanged Man from the Milanese Visconti Sforza Tarot, a Trionfi deck commisionned around 1453/1454 by the Milanese ducal Sforza/Visconti family, conserved in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York. At the right the Hanged Man from the Charles VI Tarot, a Trionfi deck probably commisionned by the Este family around 1460/1465 (maybe from a Fiorentine artist) and conserved in the French National Library (Bibliotheque national Française, BnF) in Paris. The deck is very difficult to date and to attribute, because there are no heraldic elements on this deck. The fact that two of the cards are identical to the Alessandro Sforza deck made it possible to attribute the card to Northern Italy. On the Milanese card a young man, his hands tied behind his back and hanging on his left foot, on the card from Ferrara a young man with a bag in each hand (full of money or probably) hanging on his right foot. The Visconti Sforza youngster with his legs crossed, the one of Ferrara with his second leg freely sweeping in the air. Both cards beautifully painted and decorated with gold.

The smaller printed cards of the same period have obviously less details. Very few printed cards have been preserved. Like today's playing cards, they were printed on big sheets, colored and finally cut in single cards. Sometimes the sheets contained errors and could not be used to produce quality cards. Printers did not like to waste paper, so these sheets were used for other purposes. Sometimes they were used to fill up the covers of books. When books gets older, it arrives that they need to be restored, and in some restoration cases old sheets were found back in the book bindings. These sheets are now conserved in several musea all over the world. On three of these sheets we find a complete image of the Hanged Man.

From left to right we have the hanged man from the Rothschild sheet (Rothschild was the last known private owner of this sheet) that is conserved in the Library of National Highschool of Art in Paris, the Hanged man of the Budapest sheet that is conserved in the Budapest Art Museum and finally the Hanged man of the Rosenwald sheet, conserved in the Rosenwald collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. The Rothschild sheet is the oldest known example of a Tarocchini deck. It was created around the end of the 15th Century in Bologne. The Rosenwald sheet is created in approximately the same period. Most experts attribute this deck to a Fiorentine card maker, others attribute it to Bologne. It has both elements of the Bolognese Tarochino decks and the Fiorentine Minchate decks. The Budapest sheets are generally attributed to Venetian card makers, some state that they were created in Ferrara. On both the Rothschild and the Rosenwald sheets the Hanged man is holding two bags like on the Charles VI Tarot. Note that on the Bolognese Tarocchini cards the hanged man is called the traitor (Il Traditore). On the Budapest sheet the hanged man is depicted as on the Visconti Sforza deck with his hands tied behind his back. On all three cards the second leg crosses behind the other leg. The Rothschild and the Budapest hanged mans are tied on their right foot (like on the Charles VI deck) and on the Rosenwald deck he is tied by his left foot, like on the Visconti Sforza card.

How did the hanged man arrive in the Tarot, what does he represent? It has everything to do with the political situation in Italy. The Roman Empire had fallen apart since centuries and it had not been replaced by a stable other configuration. Charlemagne had conquered the Northern part of Italy in the early middle ages, and in the 15th Century it belonged offcially to the Holy Roman Empire. The Central part of Italy belonged to the Roman Catholic Church and the Southern part of Italy belonged to the Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily. In between these three main powers some parts of Northern Italy became indemendent republics, like Venice, Genoa and Florence. The Holy Roman Emperor was also King of Italy, but in reality his influence was not that great. So the local Lords gained in importance and we see a certain number of City States that developped themselves and that were governed as a feodal state (Milan, Ferrara, Savoy), as a republic (Venice, Genoa, Lucca, Florance) or as a Papal State (Rome, Pise, Bologne). All these strong states wanted to become stronger and expand there territory. So the leaders of the City States often hired mercenaries, who were called Condottierri, to defend or extend there properties. The most often, Condotierri were powerfull noblemen with enough resources to maintain a powerful army. But Condottierri were anything but loyal. So as an example, one year they the could be paid by the Duke of Milan to fight against the Republic of Venice and the next year they could be paid by the Doge of Venice to combat the Duchy of Milan. This attitude was considered by most people as treason, because you don't change from side. But the people were powerless against these evil Lords who seemed yesterday their best friend and who became today their worst ennemy. The only thing they could do was trying to humiliate them. So the best painter that a city could pay was hired to paint him clearly recognisable on the outside wall of a public building (usually the mayor's office, the Palazzo di Podestà) as a lifesize fresco of this man hanged by his feet. These pictures were typical for the Northern Italian City States, especially the democratic republic states. They were created roughly from the 13th to the 16th Century and called Pittura Infamante (defamatory pictures or shame paintings). Because of their nature, outside paintings on a wall never lasted very long, wiped out by the elements or covered by a new fresco for some other subject. Not only traitors were the subject of Pittura Infamanta, thieves or people being guilty of bankrupty, fraud or corruption were all good to create a shame painting of them. Some famous painters who were commissioned to paint a Pittura Infamante were Andrea del Castagno, Sandro Botticelli and Andreo del Sarto. None of these pictures survived time, but from Andrea del Sarto we have some sketches he made before creating the real fresco.

From the two leftmost pictures we can clearly see how Andreo del Sarto worked. First he made a drawing of the naked human body. Then he covered the body with clothing to obtain the final picture in which he was sure that all proportions were right.

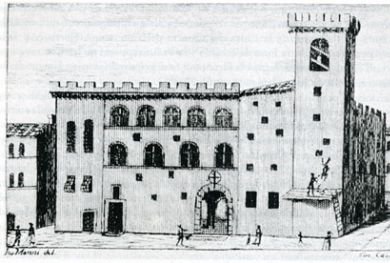

Especially in Florence the Pittura Infamante was a real expression of popular art and they continued to be created until late in the 16th Century. Here at right we see a 18th Century drawing of the Bargello Palace (the local Palazzo di Podestà) made by an unknown artist where we can clearly distinguish on the tower an artist creating a Pittura Infamante. The Bargello Palace was the usual place in Florence for these frescos.

Hanged man images are not restricted to Pittura Infamante in Northern Italy, so let us have a look at some other medieval pictures with this theme.

Here above we see three examples of 15th Century German shame paintings (Schandbild in German). The objectif of these images was the same as the lifesize frescos in Norther Italy, it was to insult someone, to shame him. Especially depicting the blason of a noble man upside down was very insulting. The leftmost picture is drawn in 1438 against Ludwig I von Hessen. The middle picture is from the same period but cannot be identified and the picture at right is realized in 1490 against a certain Hans Judman.

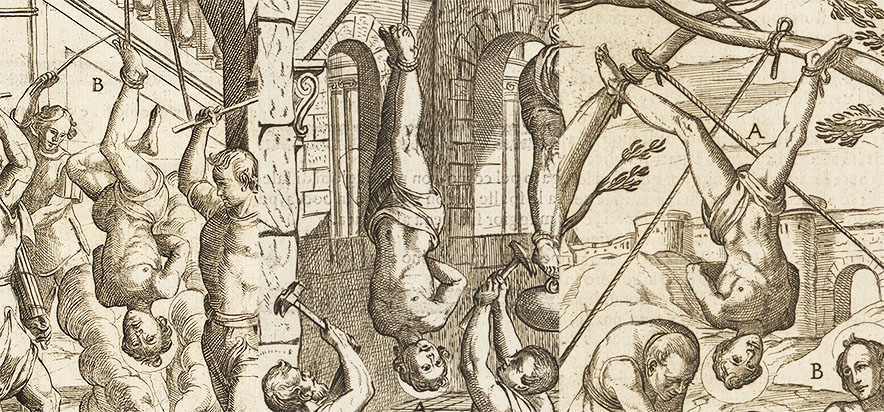

Hanging is as old as humanity. It was not only used to bring shame to someone, normally it was used to punish a person, to execute him. In 1591 a priest named Antonio Gallione wrote a book about the several methods that were used in the early ages to execute Christian Martyrs. Hanging by one or by both feet was just one of the many methods that were used. Here below details of three illustrations from this book showing the execution of some Christian martyrs. The book was called "Trattato de gli instrumenti di martirio e delle varie maniere di martoriare usate da gentili contro christiani" (Treatise on the instruments of martyrdom and the various ways of martyring used by gentiles against christians). Gentiles is a generic name for non-jewish people.

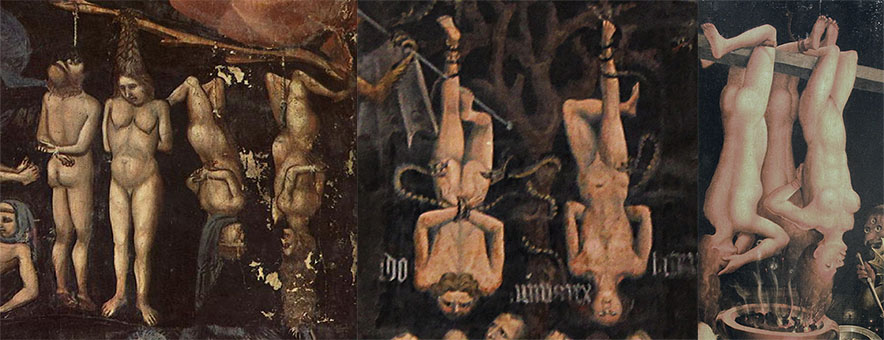

Hanging, and especially hanging upside down, was considered extremely humiliating. So in the more classical paintings it was almost exclusively depicted as part of a scenery of hell. Here below three details of much larger works, the leftmost part of a fresco painted by Giotto di Bondone between 1304 and 1313 in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, the second one part of fresco painted a century later around 1410 in the San Petronio cathedral in Bologne by Giovanni da Modena and the third detail from a painting made by an anonymous Portugese painter between 1510 and 1520 and conserved in the National Museum of Antique Arts in Lisbon.

People had clearly a lot of imagination how to hang someone. The ressemblance between the painting in the the Bolognese Petronio cathedral and the Visconti Sforza hanged man is striking, both clearly have the same source as inspiration.

Now let us go back to the Tarot and have a look how the image of the Hanged man developped from the 16th to the 19th Century, both in Italy, and in France.

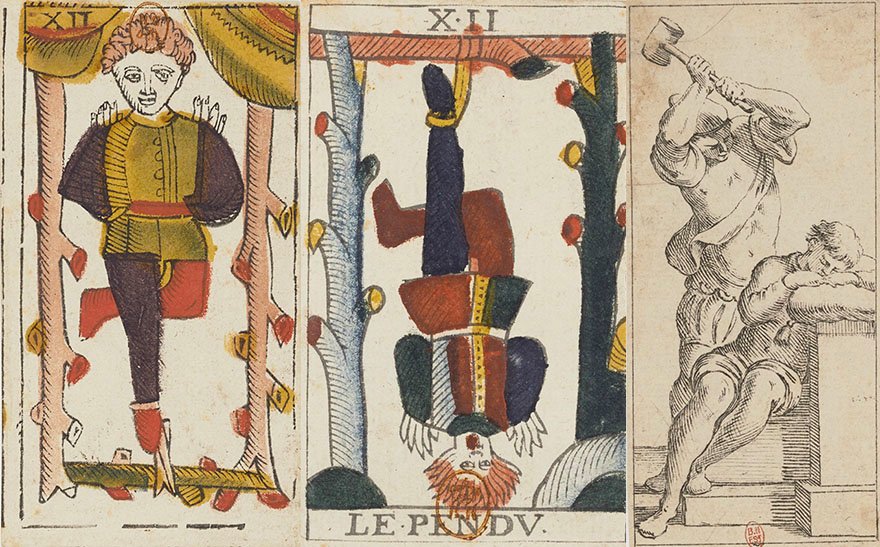

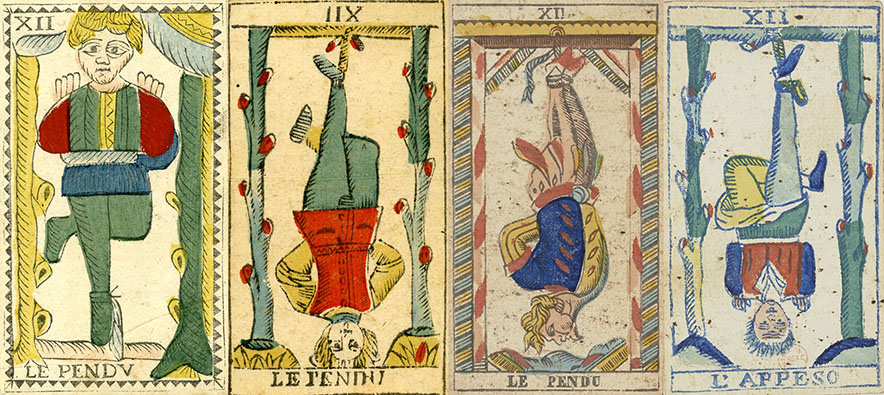

The oldest printed cards we know originate from Lyon in France. They are attributed to a certain Catelin Geoffroy and have been dated to 1557.The next two cards could not be exactly dated but are generally attributed to the beginning of the 17th Century. Both are created by anonymous artists. In the middle we have the so called Tarot of Paris and at the right the Hanged Man of a very early Tarocchino deck created in Bologne in Italy. Both decks are conserved in the BnF. On the two French cards the number XII appears, that is identical to the numbering system of the later Tarot of Marseille. On the Tarot of Paris we even see the name of the card that appears, Le Pandut (the hanged man). On the Tarot of Catelin Geoffroy the Hanged man is tied by both feet, on the Tarot of Paris by his left foot and an the Tarocchino deck by his right foot. The Italian card is loyal to the local traditions and presented without a name nor a number. From later in the 17th Century we have shown here below three other surviving decks, two from Paris in France and one from Bologne in Italy.

From left to right we have the Hanged man from the Tarot of Jaques Vievil, created around the middle of the 17th Century in Paris, the Tarot of Jean Noblet, created in the same period or a couple of years later (1659 according the BnF) also in Paris and finally the Tarocchino of Giuseppe Mitelli, created between 1660 and 1665 in Bologne. All three decks are conserved in the BnF.

Jacquel Vieville was actif as a cardmaker (engraver) from 1643 to 1664. The Vievil deck as I will call it, has a strange Hanged man. The strange thing about it is that or the numbering is on the right place and the Hanged man seems dancing (like we see on the image here above), or the Hanged man is in the right position but then the number is inversed and on the wrong position. Both opinions have there adepts. Personnaly I consider the Hanged man is in the right position (so inversed with respect to the image here above) and that the number has been reversed to emphasize the upside down position of the Hanged man. In that case he is hanging from his right foot and we see part of his hands that are tied behind his back, below his shoulders. His left leg is crossed behind his right leg.

Jean Noblet was active from 1659 to approximately 1677, his deck is considered to be created in the earliest years of his career. The pattern on the back side of his deck is identical to the one on the Vievil deck and on the anonymous Tarot of Paris. Also the coloring technique of the three decks is very similar, so maybe they originate from the same printing press. The Noblet deck is considered to be the oldest preserved Tarot of Marseille deck, but it does not really fit in the Type I or Type II classification. The cards are also much smaller than the other Tarot of Marseille cards and also some of the images have striking differences with the later cards. The image on the Noblet card is very similar but mirrored with respect to the Vievil Tarot, with the same hands appearing below the shoulders. But in contrast to the Vievil card, the hair of Noblet's Hanged man is really hanging down.

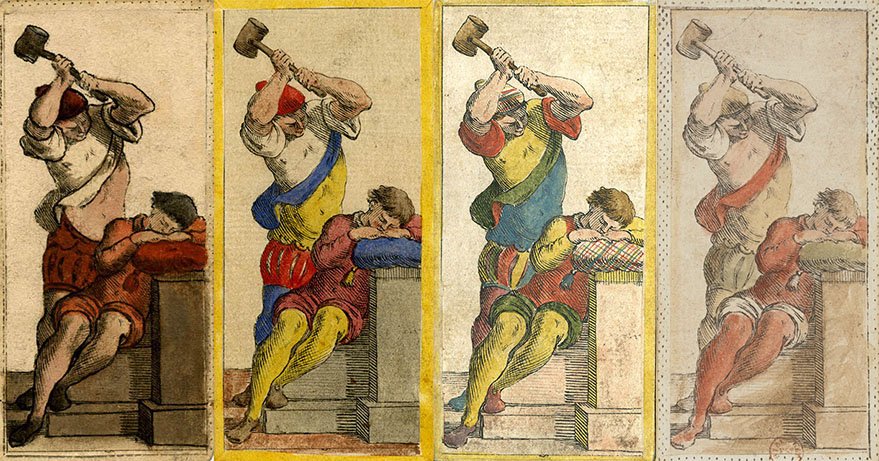

The Mitelli deck had been commissioned by the wealthy Bolognese Bentivoglio family, that was longtime the ruling family in Bologne. As we saw above, in Bologne the card was not called l'Impiccato but Il Traditore (the Traitor). Mitelli did not follow the tradition on the other cards, he created a real traitor, ready to kill a sleeping man. Giuseppe Mitelli did not color his cards, he delivered them uncolored to his clients like we see in the card here above. Mitelli must have delivered several card decks to the Bentivoglio family. The coloring was done by artists hired by the client himself, so different colored versions exists and every deck is unique. Here below we have four different examples. The first three cards are from decks that are conserved in the British Museum and the fourth one is like the non colored card here above part of the collection of the BnF. The Tarocchino deck of Giuseppe Mitelli is the oldest card deck in the Tarot family of which several complete decks survived time. Other examples with different color schemes exist. We have to admit that this deck is a real piece of Art.

In Italy in the 16th and 17th Century Tarot related card making concentrated itself in the regions around Bologne and Florence. The Northern provinces used more and more the 52 card deck with French symbols and without separate trump cards to play games. Here below some other examples from 17th and 18th Century Italy.

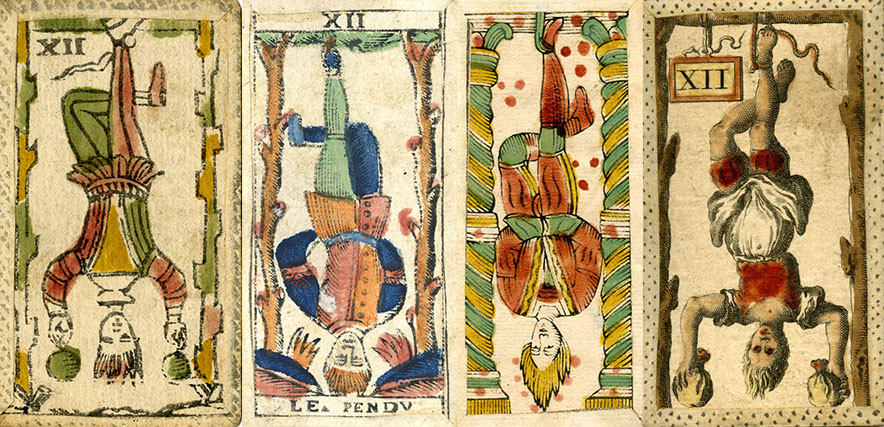

From the left to the right we have a 17th Century Fiorentine Minchita card, a 17th Century Tarocco di Bologna, a 18th Century Bolognese Tarochino card made by Angelo de Maria and a Fiorentine Minchiate card made between 1712 and 1714 by a certain Giovan Molinelli. This particular deck is printed on silk ank like the Mitelli deck the cards are hand painted and we have decks with different color schemes. The Minchiate cards follow the symbolism of the Charles VI Tarot and the Rosenwald sheet with the Hanged man holding two bags full of money. The other two decks are more in line with the Visconti Sforza deck. The Tarocco di Bologna is the oldest known Italian Tarot deck of 78 cards using French titles. The Tarocchino deck is the only one that persist not displaying the number of the card. On none of the original Italian cards we see the title of the card, only on the Tarocco di Bologna, a derivate of the French Tarot of Marseille cards, we see its name (in French!). Like on the card of Jean Noblet, all cards clearly show the hair of the victim hanging down. On the Tarocchino card it looks like that the hands of the Hanged Man are tied in front of him. On three cards the figure is hanging on his right foot, on the Tarocco card he is hanging on his left foot. In the same period in France there is a lot less diversity in the different cards, the model nowadays called the Tarot of Marseille is imposing itselves. But the desorder created by Vievil continues to infect the Tarot.

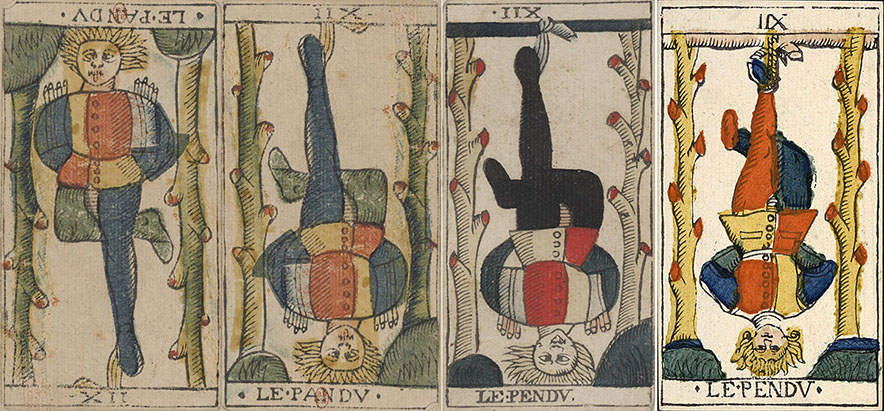

The first two cards are the same, it is the Hanged man of Jean Dodal created in 1701 in Lyon. Why is one of the two cards upside down and which one is upside down? This last question seems easy, the one at the left. But is this true? On the left card the number XII is written correctly, just like on the Vievil card. On the right card LE PANDU is written correctly and the Hanged man is hanging. The answer is maybe on the backside of the cards. The pattern here at right is the pattern used on the Dodal cards. The are like little mountains. The particularity is that the mountains allways point to the top of the card. You can compare any card, trump cards, court cards and pip cars, the pattern is allways pointing upwards.

And here is where the surprise comes, the card at the left is in the right position. No-one has to believe me on my word, you can control this on the webside of the BnF where the Dodal deck can be consulted: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10537343h.r=dodal?rk=21459;2. For the cartomancer this has no consequences, a Hanged man is hanging, so the right image is in the right position. However at the end of the 17th and in the beginning of the 18th Century this was a different case. So except for the much older Jean Noblet deck, all early Tarot of Marseille decks, both type I and type II, present the Hanged man in the same way. The two next cards we see are a Hanged man created by Jean-Pierre Payen in 1713 and a Hanged man created by François Hery in 1718. The deck of Jean Pierre Payen is like the deck created by Jean Dodal a typical type I deck of the Tarot of Marseille. The deck of François Heri is a typical type II Tarot of Marseille deck. Later in the 18th Century the habit changes, and starting around 1730/1740 virtually all decks are writing XII on the top of the cards. Let us have a look in the countries surrounding France how the Hanged Man presents himself.

From left to right we have examples of a Belgium tarot, A German Besançon style tarot, a Swiss tarot and an Italian Piemont style tarot. The Belgim Tarot is created in the last quarter of the 18th Century by the Brussels cardmaker Jean Gisaine. The Belgium Tarot has the Tarot of Jaques Vievil as an example. So here there is no doubt, the Hanged man is not hanging, he is standing like a ballerina on the tips of his toes. The second card is also from the 18th Century although we don't know exactly the year. On the cards is only marked "Tarots fin fait pas Joseph Krebs de Fribourg en Brisgau". So it is not sure where the cards are printed only that they ar created by a certain Joseph Krebs who comes from Freiburg am Brisgau in Germany. The third card is created by a Swiss cardmaked calles Gassmann arouind 1850 in Genève. Most trump cards are very similar to the type II Tarot of Marseille cards, but the Hanged man is a direct copy of the Lyonese 1557 Hanged man from Catelin Geoffroy. The last card has been dated to 1865 by the BnF. The deck hes been created by a certain F.F.Solesio in Genova. On the Italian deck we see now the word Apesso apearing. Appeso is the past participle of the Italian verb appendere, to hang.

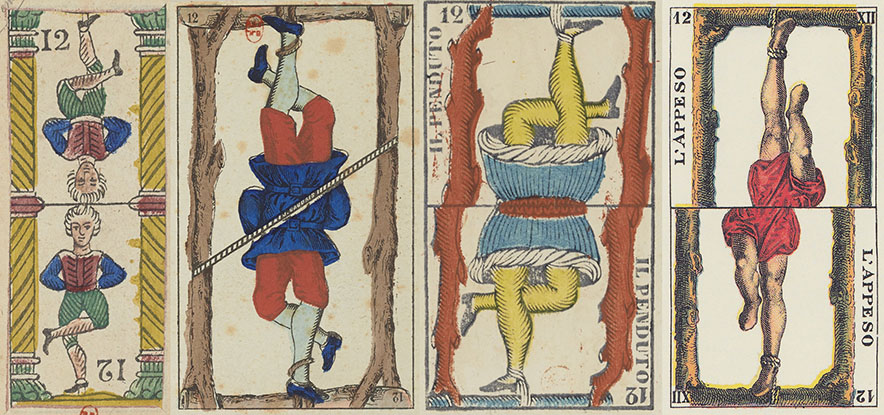

The standard playing cards with French symbols started very early to be presented as double headed cards. This was much easier for card players. The Tarot cards are not very well adapted to this representation, but at the end of the 18th Century some decks were created in this style. The first deck was around 1770 the Bolognese Tarocchino deck. Since that date all Tarocchino decks are double headed. Others followed with more or less success.

From left to right we have a Bolognese Tarocchino card dated to 1840, a Besançon type hanged man made in printed from 1860 to 1889 by J.Gaudais in Paris, a Tarot of Piemont, created by Allessandro Viassone and created around 1875 in Torino and finaly a hanged man created around 1887 by Fratelli Armanino in Genova and based on the Milanese Soprafino deck. Two are hanging by their left foot, the by the right one, two have one leg crossed behing the hanging leg, on the Tarocchino deck the leg is crossing in front of the hanging leg and on the Milanese type card the leg is free floating like on the Charles VI deck. A particularity of these decks made for card playing is that they all use Arabic numerals instead of the traditionnal Roman numerals that we have seen on all previous decks (if they were numbered).

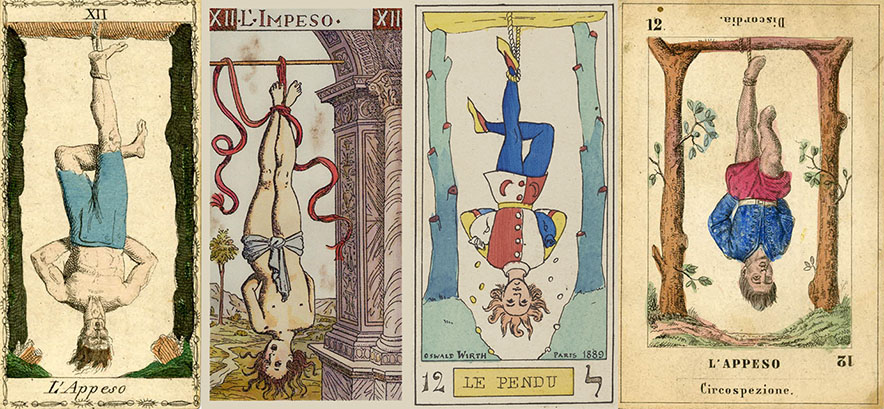

Starting from the 19th Century both double headed decks and full card images continue to exist, the first group for card playing and the second group for cartomancy purposes. On these pages we are almost exclusively interested in the last group of cards so we continue to see how they are developping. Let's have a look at some examples.

From left to right the Tarot of Lombardy created in 1810 in Milan, the Giovanni Vachetta Tarot, originally printed in 1893 in Turin, the Oswald Wirth Tarot, created in 1889 in Paris and an anonymous early 18th Century Tarocchi deck. The Vachetta deck is originally black and white, the version shown here is watercolored in 2001 by Osvaldo Menegazzi founder of Il Meneghelo, a Milanese society specialized in reproducing old card decks. The rightmost Tarocchio deck is actually conserved in the British Museum. Both the Oswald With deck and the Tarocchi deck were made as cartomancy decks. They preceded a shower of specific cartomancy decks that started in the early 20th Century with the Rider Waite Smith deck. Here below this card and some other examples/

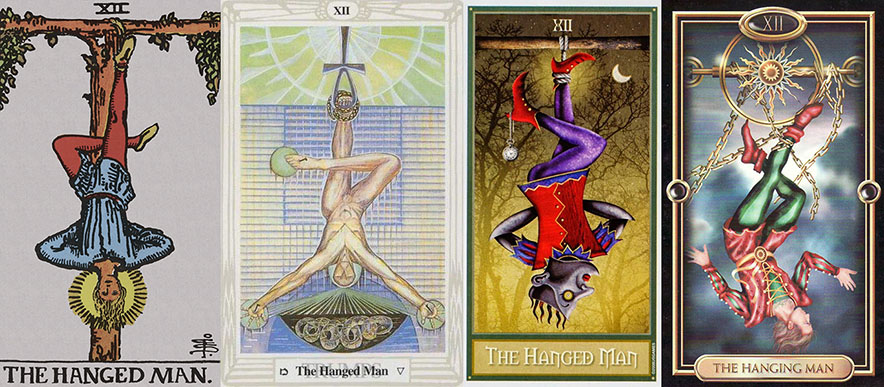

From left to right we have the Hanged man of the Rider Waite Smith Tarot (also called the RWS Tarot), created in 1903 by Pamela Colman Smith on instructions of the Golden Dawn member Arthur Edward Waite, the Thoth Tarot, created between 1938 and 1943 by Lady Frieda Harris on instructions of the Golden Dawn member Aleister Crowley and first published in 1968, the Deviant Moon Tarot created by Patrick Valenza 2008 and the Gilded Tarot, created by Ciro Macheti in 2004. With the rise in popularity of the cartomancy, the Tarot entered definitely the Anglo-Saxon world, and all card titles of shown decks are originally in English. The RWS Tarot was right from the beginning immensilly popular and many other decks were created with this deck as a base model. Other artists followed their own thoughts. In the early years only cards based on the RWS deck were accepted and Crowley could not find a publisher for his deck. It was only in the 1960s when a lot if new innovating idees embraced the world, that pulishing houses became ripe for publishing other kind of Tarot decks. And so long after their creator died, the Thoth Tarot was finally published in 1968 to become one of the most important occult Tarot decks ever published. Patrick Valenza was inspired by his childhood dreams and he created a magnificent deck that is exploring the dark side of the subconsious. The Gilded Tarot is inspired by the RWS deck, but it is one of the most gorgeous and beautifull Tarot decks ever created. Let's have a look at some more modern Tarot cards to see how they handle the Hanged Man.

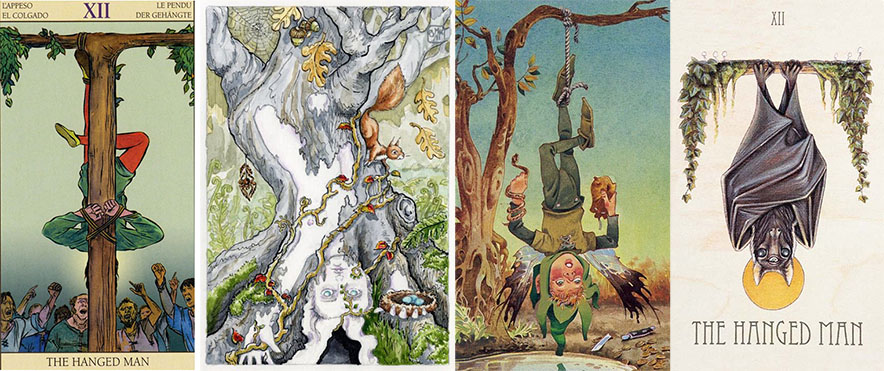

From Left to right the Tarot of the New Vision, created in 2003 by Gianluco Cessaro, the Stolen Child Tarot, created in 2012 by Monica Knighton, the Fairy Tarot, created in 2004 by Antonio Lupatelli and the Wooden Tarot, created in 2012 by Andy Swartz. On the Tarot of the New Vision we see the RWS Tarot from behind the cards. On the Stolen Child Tarot the Hanged Man is not hanging from a tree, but he is completely integrated in the tree. Tha Fairy Tarot is rather classical but transposed in the fairy world. The Wooden Tarot has the animal kingdom as a subject, so what better as a bat could represent the Hanged man.