THE TAROT WHEEL

IMPERATOR - THE EMPEROR

The head of a bearded man. His beard, split in two, and his wide hat are both typical for the Hungarian fashion in the early 15th Century. On the hat we see the imperial eagle and the face of the man is the face of Emperor Sigusmund, who was King of Hungary at 19 years old before he became King of Croatia, King of Germany, King of Bohemia, King of Italy and finally Holy Roman Emperor at the age of 65. He was called Ginger when he was young because of the color of his hair. His father was the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV from the House of Luxembourg and his mother was Empress Elisabeth of Pomerania, fourth and last wife of Charles IV and granddaughter of the King of Poland. He received his education at the Hungarian court, which customs he would conserve during his life. It is there he found his first wife and his first crown. He was crowned Emperor by Pope Eugenius IV in Rome on the 31st of May 1433. The image is painted by Bonefacio Bembo and the card is from the 1442 Visconti di Modrone deck conserved in the Cary collection of the Yale University.

Images of the Emperor do not fail to exist on the fifteenth Century cards. Not less than six handpainted cards of the Emperor survived time, four originating from Milan and two from Ferrara. We will present all of them here below.

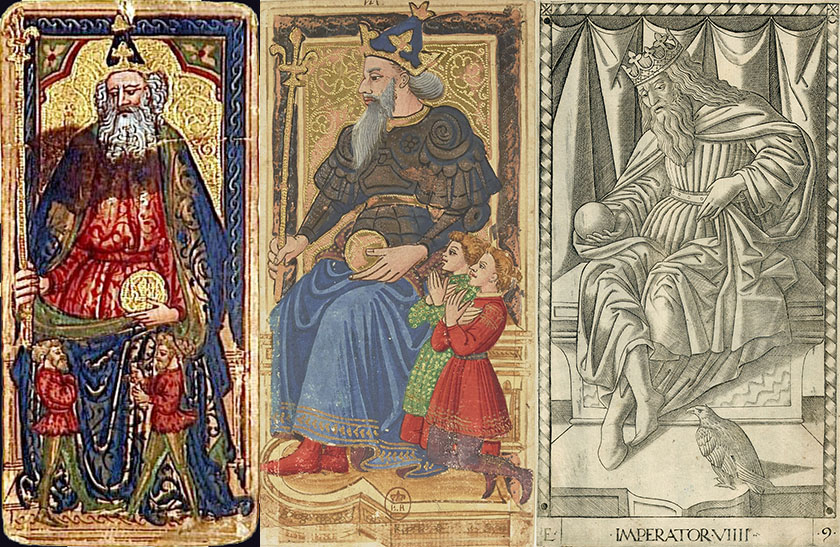

Four Emperors, the first three of them created by (according specialists, to whom I do not belong) Bonifacio Bembo in order of the court of Milan. All four Emperors have an hat respecting the Hungarian fashion of that time with the imperial eagle on the front of it, a wand of power in the right hand and the orb of power in the left hand. The first two are ordered by Filippo Maria Visconti and they represent clearly Emperor Sigismund. The first one is from the Visconti di Modrone deck, dated to 1442. The second one is from the Brera Brambillaz deck of unknown date. Personally I place the creation of this deck after the Visconti di Modrone, maybe short before Filippo Maria died. The third card is from the Visconti Sforza deck, ordered by the Milanese court when the daughter of Filippo Maria Visconti, Maria Bianca was Duchess of Milan. Here we see an old man with red shoes. While we have a new Duke (Francesco Sforza), and a new Emperor (Emperor Frederic III was crowned in Rome in 1452) this old man probably reflects the dimishing power of the Holy Roman Empire over the Duchy of Milan. The House of Visconti became Duke thanks to the King of the Romans (The father of Filippo Maria Visconti bought the title of Duke from Wencelaus IV, King of the Romans and oldest brother of the later Emperor Sigismund), but Francesco Sforza became Duke thanks to his own capabilities. The fourth card is probably a late 15th Century copie of the Visconti Sforza card. The card is conserved in the Museo Fournier de Naipes de Alava, situated in Northern Spain.

On the golden clothes of the first Emperor we see a crowned bird, an emblem for the Visconti family. The decorations on the clothes of the second Emperor are neutral, there where on the clothes of the third Emperor we see the same decorations as on the clothes of the Empress of the same deck. In the first place the Piumai, emblem of the Visconti family and next the triple ring, emblem of the Sforza family. The last Emperor has again more neutral decorations on his clothes. The two first Emperors confront us frontally, the two others are turned a little bit away of us (of us or of reality?). On the first card the Emperor is surrounded by four children in four different colors, representing the four suit colors and at the same time all the different geographic entities that make up his Empire. The boy for us on the foreground at the left has written on his clothes "a bon droit", the device of the Duchy of Milan, to confirm the loyal appartenance of the Duchy of Milan to the Empire.

On the left we have the Emperor from the Edmond Rothschild collection conserved in the Louvre in Paris. In the middle the Emperor from the so called Charles VI deck, conserved in the French National Library and at right one of the 1465 Mantegna prints, of which copies exists in several musea in the World. This particular copy is from the British Museum. Art specialist place the Rothschild card as Late Gothic (so late medieval). Its age is estimated between 1450 and 1460. The Charles VI deck however is classified as early Renaissance and dated between 1460 and 1465. What is interesting on these two handpainted cards is that we see the same scene, the Emperor holding an identical wand of Power, having an identical orb in their left hand and wearing an identical crown. There is no shield with an imperial eagle like on the Milanese cards. In fact Ferrara was as a Papal State, not part of the Holy Roman Empire, and the Emperor on the card is more generic, he could also be the Byzantine Emperor. On the Mantegna engraving however, we see a bird that references to the imperial eagle. Both handpainted cards might have been ordered by the Este court of Ferrara, but the Charles VI cards have apparently be made by a Fiorentine artist. The Renaissance started in Florence and also the border decoration of the Emperor’s clothes and the boys’s clothes is a typical style element for Fiorentine artists.

All these differences in detail were really only differences in detail. On all cards the Emperor is a bearded older man, showing clearly several objects that point to his high rank as an Emperor. Let us compare these cards with the first printed tarot cards of which some rejected uncut sheets have survived time.

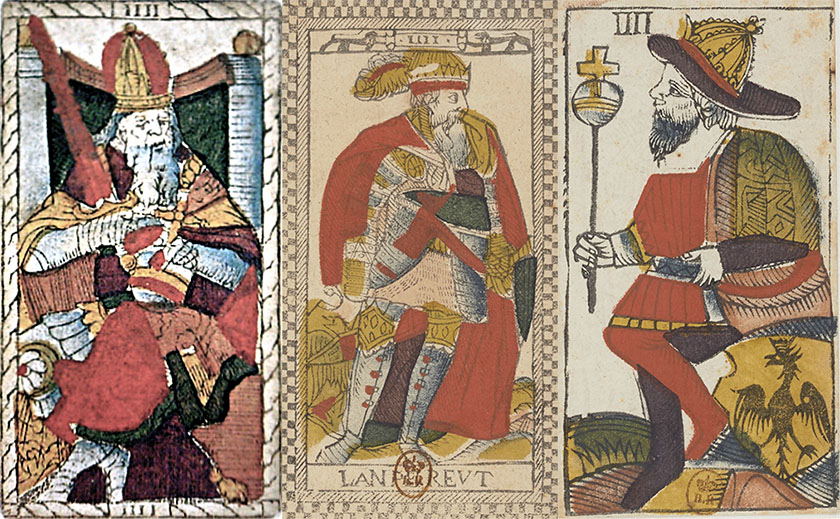

From left to right the Rosenwald sheet made by the end of the fifteeth century in Bologna, the Budapest sheet, made around the turn of the century (15th to 16th) in Ferrara and as third the Cary sheet, made in the early sixteenth century in Milan. Dating is not very precise. On the different cards again a man of power with the different attributes of the Emperor, with some differences due to the place of production of the cards. We remark that on the handpainted Charles VI deck, made for the Este court by Fiorentine artists the imperial eagle is missing while on the Budapest sheet, probably produced in Ferrara the eagle is present. We have to remark that the Este courts were as Dukes of Ferrara part of the Papal States and as Dukes of Medena part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Let us show now look at some of the representations of the Emperor in the same period.

The first representation is a golden seal, the seal attached to the Golden Bull of 1356, a decret of Emperor Charles IV to give a legal background to the election of the King of the Romans. The King of the Romans was the name given to the King of Germany, and it was the King of the Romans who could become Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, once he was crowned by the Pope in Rome. Not all Roman Kings arrived to negociate this coronation by the Pope. They had the power of the office, but not the name. It was only in the 16th Century that Emperor Charles V arrived to eliminate the need of coronation by the Pope. From then on the official title of the Emperor was Emperor elect. The great difference between the King of Germany (King of the Romans) and the King of France was that the French office was heriditary and the German office was traditionally obtained by election. Charles IV establishedin the Golden Bull a circle of seven electors, 3 Arch-Bishops and 4 Princes. Election was by majority of votes and the electors could equally well remove a King of the Romans from his office.

On the seal we see the traditionnal depiction of the Emperor, with the wand of power in his right hand and the orb of power in his left hand. At his right, a shield with the imperial eagle. But who were the Emperors important in the 15th Century?

Only three men, three faces. The first one is of Emperor Sigismund, King of the Romans from 1411 to 1437 and effective Holy Roman Emperor from 1433 to 1437. Next to him is Emperor Frederic III, King of the Romans from 1440 to 1493 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1452 to 1493. We see again the Holy Roman Emperor with his traditional attributes. The third Emperor is Emperor John VIII Palaiologos. He was Byzantine Emperor from 1425 to 1448. His visit to Italy, to the Council of Florence (that started as the Council of Ferrara but was moved to Florence because of the Plague) and to Pope Eugenius IV in 1437 had an tremendous influence on Italian society in that time. The painting was made by the Florentine painter Benozzo Gozzoli to commemorate this visit. His link to the Tarot; on the Sola Busca deck we do not have an Emperor, but we have many crowned people. All of them are wearing a crown that is identical to the Byzantine crown on the painting of John VIII.

In 1453 the Byzantine Empire collapsed and in the following centuries the power of the Holy Roman Empire would be confined to the German speaking countries. So how did the Tarot deal with the now distant figure of the Emperor?

In France, the cards starts to develop in the sixteenth Century in more dynamical and less traditional images. From left to right the Emperor of Catelin Geoffroy (1557), the anonymous Tarot of Paris (early 17th) and finally Jaques Vievil (mid 17th). In the last card, the Tarot returns to its sources, and the Emperor is depicted in a very tradional way, even including the imperial eagle of the Holy Roman Empire,

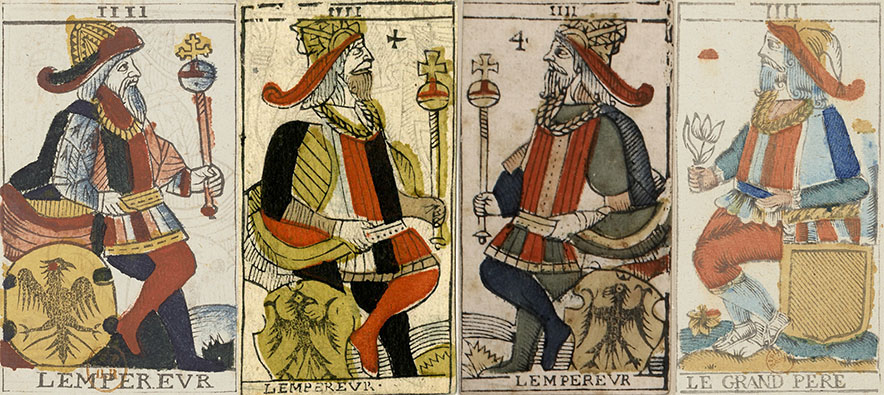

On the Tarot de Marseille, the cards became mirrored, like on the two left examples of Jean Noblet (1659) and Guillaume Debesset (18th Century). But very soon, the Emperor turned its face back to the past like on the third example made in 1701 by Jean Dodal. On the last card we have some temporary revolutionary influences that would not last longer than a few years. The card here is from the 1794 deck of François Isnard.

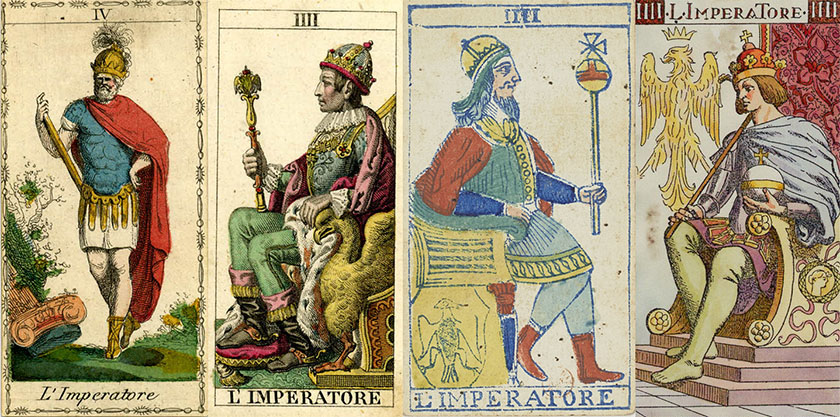

In Italy development of the Tarot family continues indepently from the Marseille Tarot. Here above four examples of the Emperor (or the corresponding card) from the Tarocchino di Bologna. From left to right we have an anonymous Tarocchino from the beginning of the 17th Century, a Tarocchino desigend around 1660/1665 by Giuseppe Mitelli for the wealthy Bentivoglio family, a Tarocchino made in the middle of the 18th Century by Antonio di Maria and a Tarocchino in Mitelli style made by Franciscus Barattini in 1803. The first card is conserved in the French National Library, the three other cards are from the collection of the British Museum. The first two cards are identical in their representation of the Emperor as the cards made in order of the Este court from Ferrara. In 1725 there was a serious conflict between the Church as Ruler of the Papal States and the City State of Bologna claiming partly independence, with as a result that the four Popes (Empress, Emperor, Popess and Pope) as they were popularly called, were replaced by four Moors of equal value. So on every Tarocchino deck printed after 1725 we encounter these four Moors, as is the case here in the decks of Antonio di Maria and Franciscus Barattini.

The Minchiate decks are peculiar in several ways. There are 20 new trumps inserted between the cards "the Tower" and "the Star". The Popess and the Pope are removed and there appear an Empress and two Emperors. The Emperors are numbered III and IIII and represent the Emperor of the West (the Holy Roman Empire) and the Emperor of the East (the Byzantine Empire). On the first line we see the Emperors from two decks from Florence. On the left we have cards from a standard deck and on the right cards from a deluxe version. On the bottom row at the left cards from a deck printed in Bologna and at the right cards from a deck printed in Rome. Remark that on the Fiorentine deluxe version the two Emperors are inverted with respect to the standard decks. All decks are printed in the 18th Century except for the deck originating from Rome, that is printed in 1823. The oldest surviving Minchiate cards are from the 17th Century, but literature sources give birth to the Minchiate in Florence in the 16th Century. All Emperors are depicted in a traditionnal way, with the wand of power, the orb of power and the Emperor's crown.

Also the 19th Century Italian Tarot cards do not change the symbolism of the Emperor. From left to right we see the 1810 Tarot of Lombardie produced in Milan, the Dellarocca Tarot, printed in the same year and the same town, the traditionnal Solesio tarot printed in 1865 in Genova and finally the 1893 Tarot of Giovanni vachetta published first in Turin. The Holy Roman Empire ceased to exist in 1806, that is maybe why we see on the 1810 Tarot of Lombardie an Emperor withour a throne and without other distinctive signs of power. The ruins next to him recall a past glory. All other cards respect the traditionnal depiction of the Emperor.

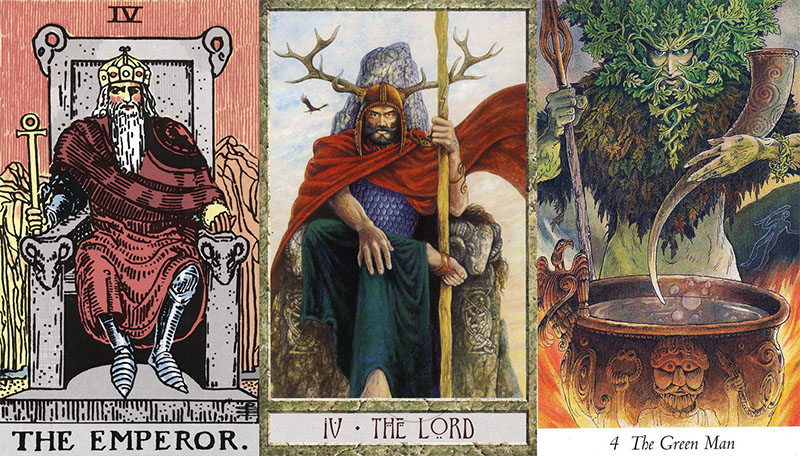

Also the Order of the Golden Dawn did not remove or change the figure of the Emperor. They only placed him further back in time, to represent Charlemagne. But modern decks can represent the male energy of the Emperor in many different ways. It can be an Emperor, but it can also be a complete different figure. From left to right we have here the 1903 Rider-Waite-Smith deck, the 2004 Druidcraft Tarot created by Philip Carr-Gomm, leader of the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids, and the 2011 Wildwood tarot created by Mark Ryan, John Matthews and Will Worthington. On the Druidcraft Tarot the Emperor is simply called the Lord. On the Wildwood Tarot the Emperor becomes the Green Man. There where the Empress expresses the tenderness of the female energy, the Empreror represents the force of the male energy. Both representations try to accentuate the male energy of the Emperor card within the theme that the authors have chosen for their respective decks.

And here ends the tour in time to see how the Emperor card evolved. In fact the card did not evolve at all, right from the beginning in the 15th Century until the occult kidnapping of the Tarot, the Emperor stayed the same. The way to represent him and the message behind the card did not change. The Emperor is a symbol of power and ultimate authority. He is the male principle and does not accept someone questioning his ultimate authority. Certainly he is a father, but first of all he is the sole ruler over a vast Empire. There is no higher secular leader on Earth and everyone has to recognize him and to obey to his authority.