THE TAROT WHEEL

IL BAGATTO - THE MAGICIAN

A bearded man with blond hair, and a troublesome expression on his face. This image is a detail from the oldest surviving card, the Conjurer from the Visconti Sforza deck created around 1454. His original Italian name is" El Bagatella", a name that can be translated as "a trifle", "an unsubstantial thing". Later this would become "Il Bagatto" or "Il Bagat",that seems to be a shorthand for El Bagatella. In France, in the Marseille Tarot, they call him "Le Bateleur", that can be translated to the Street Performer. In English, we know him best as "the Magician". But what kind of magician? A Sorcerer, a Conjurer? He is also sometimes indicated as an Artisan, a Juggler, a Trivial Performer or a Mountebank to call just some of the many names he has. Let us try to understand this figure and see how he developed over the years. We start with the two surviving hand-painted cards from the fifteenth century in Italy, one from Milan and one from Ferrara.

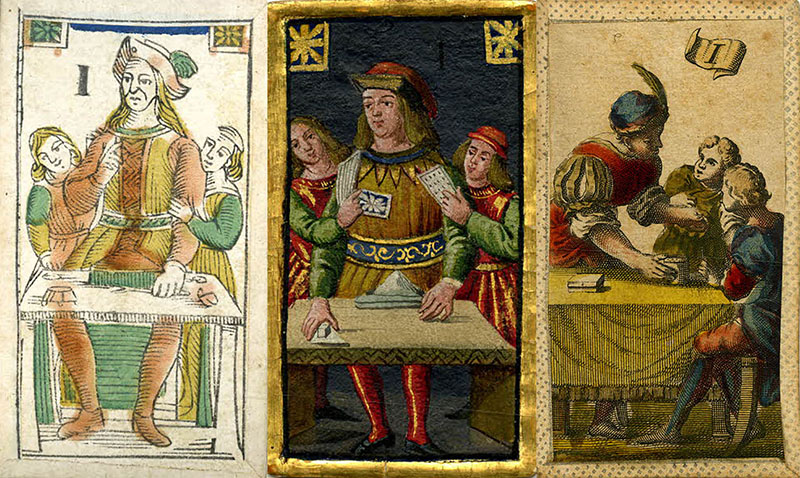

On the left the Magician of the 1454 Visconti Sforza deck, conserved in the Morgan Library in New York, and on the right the corresponding card from the 1473 Este deck, conserved in the Beinecke Library of the Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. On both cards, we see a man, richly clothed in red, behind some sort of market table.

The Visconti Sforza card is particular interesting. We see a very serious man with a troublesome expression on his face. He is certainly not there to make the people laugh. He is clothed from top to toe in a red dress, that represents a high social status. The dress and even his hat are edged with ermine, which indicates a royal origin. On the table in front of him, we see five different attributes. First there is a hat, an attribute often used by conjurers to hide objects. The other four objects represent the four suit symbols. Two coins, representing the suit of Coins, a cup, representing the suit of Cups, a knife, representing the suit of Swords and finally in his hand a wand representing the suit of Batons. It is only many years later, with the occult Tarot decks, that it would become common practice to show these four objects on the table, and nothing more. The four suit symbols in this image represent the four elements, so this man is not a simple conjurer, he is the master of the elements.

The Magician on the Este deck has more of a trickster. He is doing tricks to amuse the children in front of him. On this scene, we are clearly on a village fair, like the Fool of the same deck, where we see the same children.

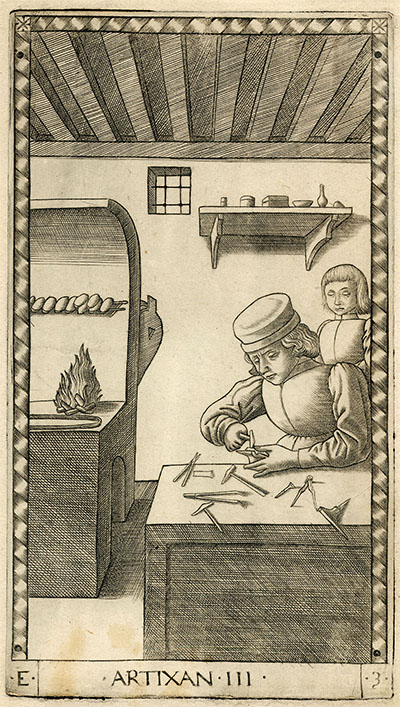

In the same period as the hand-painted cards are created, some unknown artist creates the Mantegna engravings, a series of 50 cards with a similar vocation as the Tarot Trumps. There are many similarities between the two sets of images. The 50 engravings are divided in 5 groups of 10 cards each, the first group showing the different levels of society, starting with a poor man (MISERO, see the page about the Fool) going up until the Pope. This is very similar to the first group of six Tarot cards that go from the Fool to the Pope. On card n° III (all Mantegna cards are numbered) we see an ARTIXAN, a craftsman. This particular print is dated to 1465. Behind the artisan, one of his apprentices, who is looking carefully at what the master is doing. In the Renaissance, schooling was rare, and most young people learned their job directly from a skilled craftsman. The different professions were organized in powerful guilds, and each guild had its own rules and practices. There were local guilds, limited to one single City State, but there were also well-organized guilds which influence extended all over Europe. The printers' guild is an example of this last category.

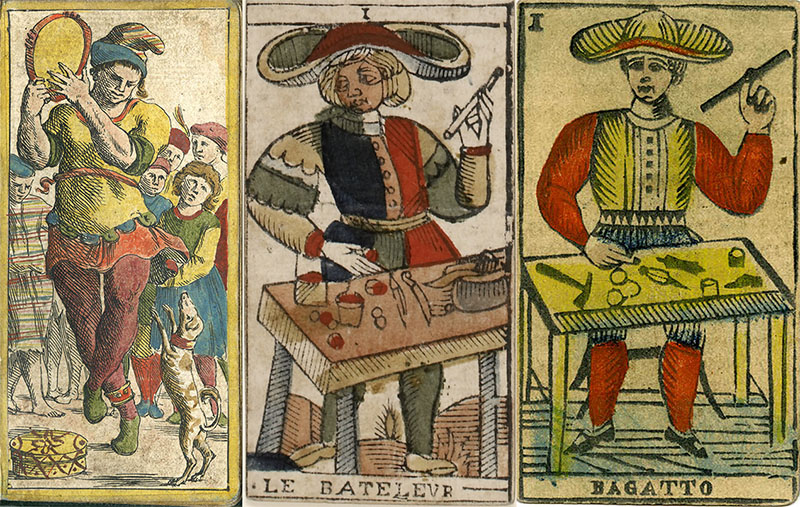

Several uncut sheets found in old book bindings, are dated to approximately the end of the 15th Century, contain a card representing the Magician. From left to right the Magician of the Rosenwald sheet, conserved in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. and probably printed in Bologna. Next the same card from one of the Budapest sheets, conserved in the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts with its origin in Ferrara and finally the corresponding card from the Cary Sheet, conserved in the Beinecke Library in New Haven, generally attributed to Milan. We remark that the number I is written on the first two cards. These cards were made for a mostly illiterate public. These people ignored the more profound meaning of the cards, so they needed, that certain cards were numbered, to be able to memorize the game sequence of the trumps.

The Rosenwald deck does not have a Fool, but the Magician is wearing a fool's cap, so this card possibly represents both. On all three cards, we see a man behind a table with some mostly unidentifiable objects in front of him. On the Budapest deck, there are four spectators behind the Conjurer. Except of some minor details, the three images are very similar.

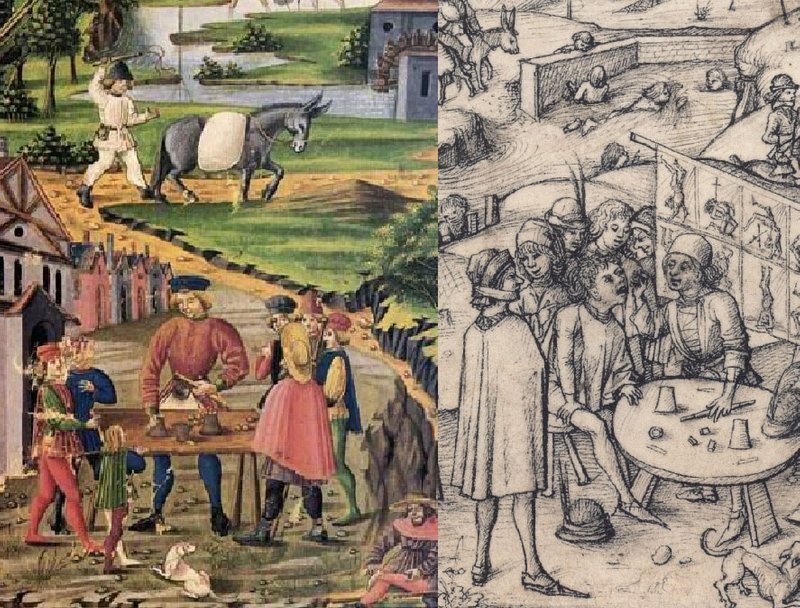

But how did contemporary artists portray a conjurer? It is not a subject very popular in Renaissance Art. There is apparently no link with Religious Art or with Classical Art. Still, there are some examples. Let us begin with the Conjurer, portrayed by the Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch, somewhere between 1475 and 1480.

The man opposite to the Conjurer is fascinated by what the Conjurer is doing. An assistant of the Conjurer is stealing at the same time the purse of their victim. It is clear that the Conjurer did not have a very positive image.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, another Dutch painter, paints in 1569 the same subject. The image here below is a detail of a religious painting, called "Christ driving the traders from the Temple"

This time not a Conjurer but a Mountebank. He has just removed a rotten tooth from a woman, and a crowd of people is watching what he is doing. The Conjurer's assistant tries to steal a purse, but he is caught by a guard behind him. Again, a very negative view on the subject.

In the fifteenth century, Astrology had an important place in the sciences. In fact, the word astronomy did not exist yet, and astrology was the science that concerned the study of the heaven. The seven known planets (Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn) had an influence on everything that happened on Earth. Artists visualized these astrological principles in a series of seven images, one for each of the planets. It is the first image, the Children of the Moon, that is of the greatest interest to us. Here below two examples, the first one created around 1465 by Christoforo di Predis and the second around 1480 by Meister Hausbuch.

And again two times a street performer or a mountebank. It is obvious from the images of popular art that the Magician, as we call him, had in the Renaissance a very low ranked place in society. He is depicted as a mountebank or at best as a conjurer. Often he is a partner in crime with pick pockets. He is certainly not the powerful magician that the French occultists made of him. For this reason, I prefer to call him a conjurer or more general a street performer. The only exception seems to be the Visconti-Sforza deck, where the street performer is also the guardian over the suit symbols. The 16th and early 17th Century would produce decks that continued the same tradition.

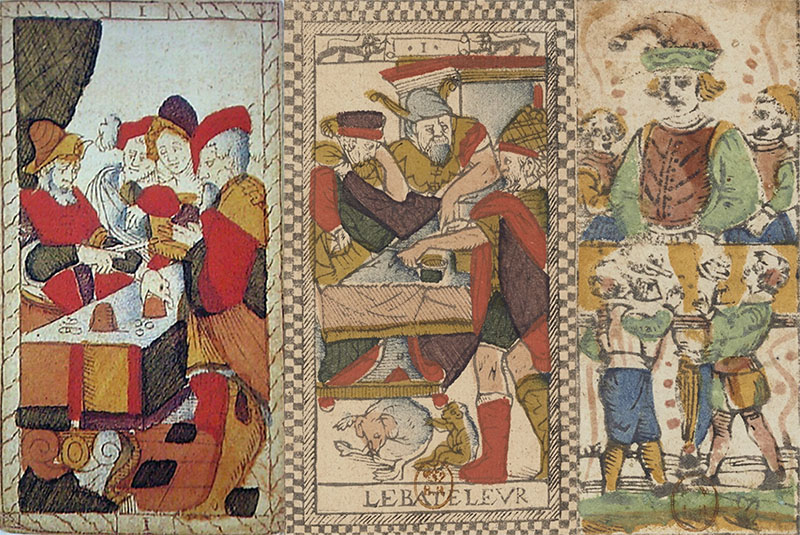

From left to the right the 1557 deck from Catelin Geoffroy, produced in Lyon in France, the anonymous early 17th Century deck called the Tarot of Paris printed in Paris in France and a 17th Century anonymous Tarocchino deck produced in Bologna in Italy.

The deck of Catelin Geoffroy is an atypical Tarot deck. Lyon, where it was produced, was an important printing center in Europe. On the card, a very dynamic image, that looks like a picture from daily life, we see a trickster performing an act of switcheroo. People can bet under which cup a certain object can be found. Usually, it is the trickster who takes the money that could be earned. The suit cards of this deck are based on the 1544 German Virgil Solis deck. Virgil Solis was a draftsman and printmaker living in Nuremberg. He used as suit symbols parrots, pawns, lions and monkeys. There are only three court cards, a soldier, a queen and a king, with kings and queens sitting on a horse. In the border of the cards on the top and on the bottom a number. The deck has 12 trumps surviving. The numbers on the cards follow the same order as the Tarot of Marseille.

Although using standard suit symbols, the Tarot of Paris has many similarities with the deck from Catelin Geoffroy. Especially, it is using the same dynamic drawing style. On the top, below the border, a number that follows the Tarot of Marseille rules. Like on the previous card, we see a trickster doing gambling games with an adult audience.

The Conjurer on the Tarocchino deck is continuing the tradition of the Este deck. The Conjurer is not doing gambling games, but he is performing some tricks to amuse his child audience. On his head, we remark a party hat with a bell on the top, just like on the fool's cap that the Conjurer of the Rosenwald deck is wearing. In Italy, evidence for the existence of a deck of 78 cards, had completely disappeared. On the axis Bologna Florence Tarot-based games continued to live, Tarocchino in Bologna and Ferrara and Minchiate in Florence and Bologna, although also Rome made cards are known. Like the Tarot de Marseille, the figures on the standard Tarocchino cards did not change over the centuries.

Later in the 17th and 18th Century, we have many Tarot decks surviving, most based on the Tarot of Marseille imagery. Let us start to show three variations on the Minchiate theme.

The first card is drawn in the standard Minchiate design. This particular deck was produced in Bologna, but Florence was responsible for this design and produced the same kind of cards. The second card is a very luxurious version of this deck produced in Florence. The last one, also produced in Florence, is a later variation on the theme that is very close to the earlier Este deck. On all three decks we see a Conjurer doing tricks to amuse his child audience, typical for all the decks produced in Ferrara, Bologna and Florence.

On the following example, we see an a-typical Tarocchino deck and two versions of the Marseille Tarot.

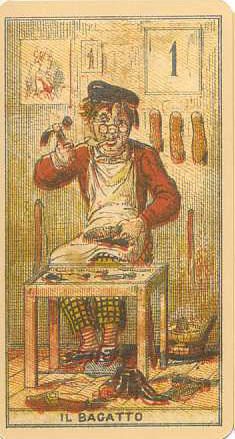

On the left side, the street performer, a card from a hand colored Tarocchino deck conceived by Giuseppe Mitelli around 1664 for the rich Bolognese Bentivoglio family. Although the theme is handled in a very original way, we still see a street performer that is amusing his child audience. S,o the card expresses the same thing as other Tarocchino decks. In the middle we have the famous Tarot de Marseille made by Jean Dodal in 1701 in Lyon, a town that continuous to be one of the most important printing centers in Europe. The Conjurer is now alone without spectators, which will be the norm for many years to come. The Tarot of Marseille is systematically printed in mirror, so in his right hand he is holding a wand and in his left hand a coin. On the table a cup, a knife, and many other objects. The image of the mountebank has left us for good, the Conjurer became a respectable person. On the right side, a deck made by the Torino-based printer Rossini in the second half of the eighteenth century. The general atmosphere is identical to the Tarot of Marseille. Special about this deck is that Rossini was the first printer who made two different language versions of his decks, some with Italian titles and others with French titles. Another particularity of this deck is that on the table several tools are appearing, like a hammer and a form shape of a foot used by shoemakers, a particularity it shares with other decks from North Western Italy. So, the Bagatto becomes here more and more a craftsman, shifting further and further away from a mountebank or a juggler.

In the 19th Century, the Minchiate game dies out. The Tarocchino stays popular, but becomes double-headed. The Tarot of Marseille continues for some years to dominate in all its different flavors. In the middle of the 19th Century the interest in France for the Tarot the Marseille disappears, to make place for French suited suit cards (Diamonds, Hearts, Spades and Cloverleaves) and randomly illustrated trump cards. The French occultists start to produce their own decks.

Four Magicians / Street Performers. Each of the interpretations is very different. The first card is the Italian Dellarocca Tarot dating from the early 19th Century. The image is very similar to the Marseille Tarot, but instead of having a Conjurer or Street Performer, we see here an artisan, a craftsman, a shoemaker to be precise. Instead of holding a wand or one of his tools in his hand the Bagatto has a glass of red wine. The color of his nose and cheeks makes clear that he consumes more of this wine than the average person. In this case, our Shoemaker might not be a mountebank, he is certainly not worth a lot more than that.

The second card is a mid 19th Century copy of the late 18th Century French Etteilla cards. Here we do not see a Street Performer, but a real sorcerer. For the first time, he is named "the Magician". From someone living on the edge of society, the Conjurer is transformed in a mighty Magician.

The third card is from the Swiss occultist Oswald Wirth. The image is very similar to "Le Bateleur" of Jean Dodal, but now the four suit symbols are clearly present on the table. The Street Performer regains his position as a guardian of the suit symbols, a position he had on the oldest-known Tarot deck, the Visconti Sforza Tarot. Remark also the red flower on the ground, replacing the leaf on the Dodal card.

Finally, to the right of the text we have the Bagatto from Perrin, a Tarot made around 1865 in Torino. The design is loosely based on the Dellarocca cards, but with its own interpretation. Like in many other cards from the Piemont region, we see a craftsman behind a table. But this time he is working like on the Mantegna engravings, he is no street performer anymore, he is a real shoemaker at work in his workshop.

Let us end the development of the card representing the Conjurer / Magician with three examples of 20th Century cards. First the Rider-Waite-Smith magician, followed by two other cards made in the Golden Dawn tradition.

The RWS deck builds on the propositions of both Etteilla and Oswald Wirth. The Conjurer has become definitely a Magician, and the large majority of modern Tarot Decks follow this interpretation. On the table in front of him the four suit symbols, with as a remark that the Coin has been transformed in a Pentagram, an important attribute for the occultists. His arms are spread out, one in the air, the second pointing to the ground, forming as such the famous phrase "As above, so below", a phrase that finds its origin in old magical textbooks.

The second example is from the Tarot of the Sephiroth, created by Dan Staroff and published in 2001. This particular Tarot deck tries to unite the Tarot and the Qaballah. The third card is from the Initiatory Golden Dawn Tarot, an original creation made by the artist Patrizio Evangilisti under guidance of the famous Tarot specialist Giordano Berti. This in 2008 published Tarot deck is inspired by the mythical Golden Dawn Tarot of Robert Wang / Israel Regardie, who were inspired by the works of the Golden Dawn founder S.L.MacGregor Mathers.

Many other cards could be shown here, the Tarot in the 20th and 21st Century has taken many forms. I will content myself for each following Trump card to show the RWS card and two cards from randomly chosen other modern decks.

As a summary, we see that the Conjurer started his life as a Street Performer. On the Visconti-Sforza deck, he was a serious person and guardian of the suit symbols. Rapidly, this image degrades to a mountebank, who works together with pick pockets to make his earnings. In the early Tarot cards he is very close to the Fool, and they often work both as a street performer on the same village fair. An example is the 15th Century Este Tarot. The Tarot of Marseille gives a deeper significance to the card, here you don't look at an image anymore, but in a mirror to your own Soul. The Bateleur shows you what is potentially inside yourself. As such the Trickster is a warning, you can think of yourself that you are good, but everyone has his weak spots, so be careful, What you think that you are doing in the benefit of others might be something that you do just to pleasure yourself. The French occultists transform the image of the trickster in the Marseille Tarot into a powerful Magician. The Magician of the RWS deck will be the model for the card significance in the majority of modern card decks. When reading the Tarot, choose carefully your deck. Not every deck has the same power. I'm using by preference the Tarot deck of Jean Noblet. Being the first deck who transformed the allegories exhibited the older decks in a mirror that allows you to look in the deepest parts of the Soul, it does this in the most effective way. However, this is just my opinion, use the decks that is closest to your inner self. And take care, decks are very different. Just to name an example, the Street Performer on the Tarocchino deck of Giuseppe Mitelli does not at all exhibit the same values and significance as the Magician on the Initiatory Golden Dawn Tarot.